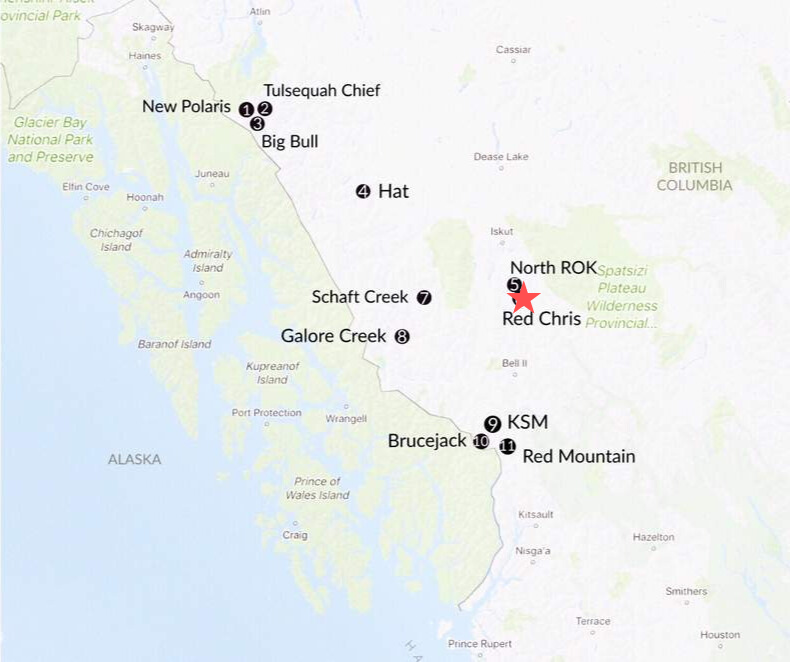

Last month, three contract drillers—Kevin Coumbs, Darien Maduke, and Jesse Chubaty—were safely rescued after spending over 60 hours trapped underground at Red Chris, a Newmont-operated copper-gold mine in northwestern British Columbia. Two rockfalls had blocked the access tunnel, but the men reached a steel refuge chamber stocked with food, water, and ventilation—built precisely for emergencies like this. They were eventually rescued using a remote-controlled scoop loader, guided by drone footage confirming the area’s stability.

This near-miss is a stark reminder: environmental assessments (EAs) are not just about protecting ecosystems. They can be critical tools for saving lives.

Beyond trees and salmon: People first

Environmental reviews are often seen as exercises in identifying and finding ways to reduce impacts to wildlife or water. But under B.C.’s Mines Act and the Health, Safety and Reclamation Code, EAs also require companies to identify and reduce risks that directly impact worker health and safety—including poor air quality, water contamination, noise, and geohazards. When a project is approved, provincial Ministers may issue an Environmental Assessment Certificate (EAC) that includes legally binding conditions to manage these risks.

At Red Chris, the refuge station was located more than 500 metres beyond the collapse zone and could sustain 16 people for 72 hours. That kind of preparedness isn’t an afterthought—it’s baked in at the planning stage.

How Environmental Assessments protect workers

Environmental assessments can help safeguard miners in several key ways when done well:

Geotechnical and hydrological hazard mapping identifies landslide, collapse, and flooding risks, guiding tunnel design and emergency routes.

- Ventilation and air quality planning ensures breathable conditions in case of disaster.

- Emergency infrastructure like escape routes, communication systems, and remote rescue access stems from early EA hazard profiling.

- Monitoring programs often include data on rock stability and groundwater pressure, which helps safety engineers act quickly.

At Red Chris, drones assessed the debris mound after the collapse and helped identify a safe corridor. A tele-remote scoop loader was then used to clear the path while keeping rescue teams out of danger.

EAs identify key hazards and infrastructure needs, which guide the implementation of capabilities such as drone assessments and remote rescue equipment by mine operators as part of their safety management systems.

The risk of rushing

The B.C. government has labeled Red Chris expansion as a fast-tracked critical mineral project, part of a $20 billion push to boost jobs and reduce U.S. tariff exposure. In fact, those rescued were working for Hy-Tech Drilling helping explore and sample the expansion area where Red Chris wants to block-cave mine (a method currently only used at New Afton Gold in B.C. – where terrain instability has been an issue). While speed may be economically attractive, it must not come at the cost of safety.

Environmental reviews are often dismissed as red tape—but skipping or skimming site condition assessments and safety analysis can lead to inadequate designs, missing infrastructure, or unvalidated hazard zones. Emerging fast-track policies must not water down requirements for geotechnical review or emergency systems.

Without full EAs, critical elements—like refuge chambers or robotic rescue tech—could be minimized, delayed, or omitted altogether.

What B.C. must do

To ensure safety doesn’t fall through the cracks, the province should:

- Tie EA completeness to worker safety outcomes: Fast-tracked projects must still meet full standards for geotechnical analysis and emergency planning.

- Strengthen oversight through independent inspectors: Independent experts should be involved from the start, not just after something goes wrong.

- Ensure transparency in hazard mapping: Community and Indigenous stakeholders deserve access to the same technical data influencing worker safety and land stability.

- Maintain real consultation—even on tight timelines: Speed must not replace engagement with First Nations, local experts, and affected communities.

- Mandate testing of rescue systems: Equipment like Red Chris’s remote scoop loader must be fully operational and verified before operations begin.

- Ensure whistleblower protection: It is critical that workers have the ability to refuse unsafe work and raise safety issues without fear of repercussions.

Safety by design

Newmont, the mine’s operator, noted, the rescue operation was “carefully planned and meticulously executed.” While we will know more after Red Chris and the regulator conduct investigative reports on the incident, the steel refuge that kept the workers safe more than 280 meters below the surface, was a result of planning and adherence to safety frameworks embedded in the EA process. If geotechnical modeling or refuge chambers had been omitted during EA and safety planning stages to save time or money, this story might have ended in tragedy.

Environmental Assessments: Worker safety starts on paper

Environmental reviews are often seen as tools for protecting nature (or mitigating impacts). But one of their important functions is safeguarding people. The Red Chris rescue makes that clear: when EAs include geohazard mapping, ventilation systems, refuge infrastructure, and emergency planning, they protect more than landscapes—they help save lives.

In fact, B.C. needs to further strengthen EAs to ensure more robust requirements for understanding site conditions before EA approval, permitting and construction to prevent pollution and waste water seepages and collapses like at Red Chris.

If B.C. wants to accelerate mining, it must not dilute the scope or depth of its EAs. It must double down on them. Because fast-tracking should never mean by-passing safety—especially when worker lives are on the line.